Everything you need to know about renovating a listed building

January 17, 2017

We talk to RIBA accredited Conservation Architect Sarah Khan and award-winning architect, Jonathan Clark about the challenging but rewarding process of renovating a listed property.

Things you need to know from the offset

“All old buildings are living buildings,” Sarah tells us. “And each period of change leaves its mark.”

Undertaking such a project is never going to be easy, but Jonathan Clark reassures us: “Things that at first seem impossible can be negotiated, and you can find your way through the maze when you work with the right professionals.”

“The most common misconception people have is that just the façade of a property is listed,” Sarah Khan tells us. In fact, if a building is listed, its entire structure is protected as well as its internal features, meaning that any change will require listed building consent and often planning consent too. Preserving the special historic interest and character of listed properties requires skilled professionals and expert care; standard buildings insurance does not provide sufficient cover during renovation work.

“It’s important not to take for granted that you can do whatever you want,” Jonathan Clark explains. “At my architecture firm, we’ve had listed and planning consent applications refused before for no good reason, although we’ve gone on to the have the refusals successfully reversed by appealing to the Government Planning Inspectorate and arguing our client’s case.”

We’re told by Sarah Khan that you should be prepared for any potential surprises that could be hidden in an old building, although an expert advisor will help you anticipate these. An example of uncovering the unexpected can be seen in a project she undertook involving a Grade II listed semi-detached house in Hampstead. During the work, Sarah encountered a blank modern interior, which was actually concealing an almost complete original interior, albeit in need of much repair.

‘’One of the most crucial aspects is to understand how an old building works in terms of its materials” she told us. ’’Old buildings will have been constructed using lime mortars and plasters, allowing it to ‘breathe’ and letting moisture evaporate. Too often these have been replaced in the twentieth century with cement pointing or plaster, creating semi-sealed enclosures. When water comes in through cracks it becomes trapped. If at all possible, removing and replacing these cementitious materials with lime can be hugely beneficial in terms of the longevity and comfort of the building.”

Finally, it’s wise to be realistic about cost and prepare yourself for the fact that the use of cheap, modern materials will often not be possible. This is because you will usually be required to make repairs using like for like materials.

The ins and outs of consent

Sarah Khan explains: “Works to the interior of a listed building only require listed building consent, which can be obtained by submitting an application to the council. But if you plan on doing work to both the interior and exterior of the building, you’ll also need to apply for planning permission. Although listed building controls take precedence, if your listed building is in a conservation area, you may also need to take this into account.

“Bear in mind that the ‘setting’ of a listed building is protected even if it isn’t situated within a conservation area. As a result, even ancillary buildings can be protected and individual trees in its garden are deemed to have tree preservation orders (TPOs) attached to them. To find out everything you need to know about your listed property you can contact your local council.”

Be prepared to negotiate

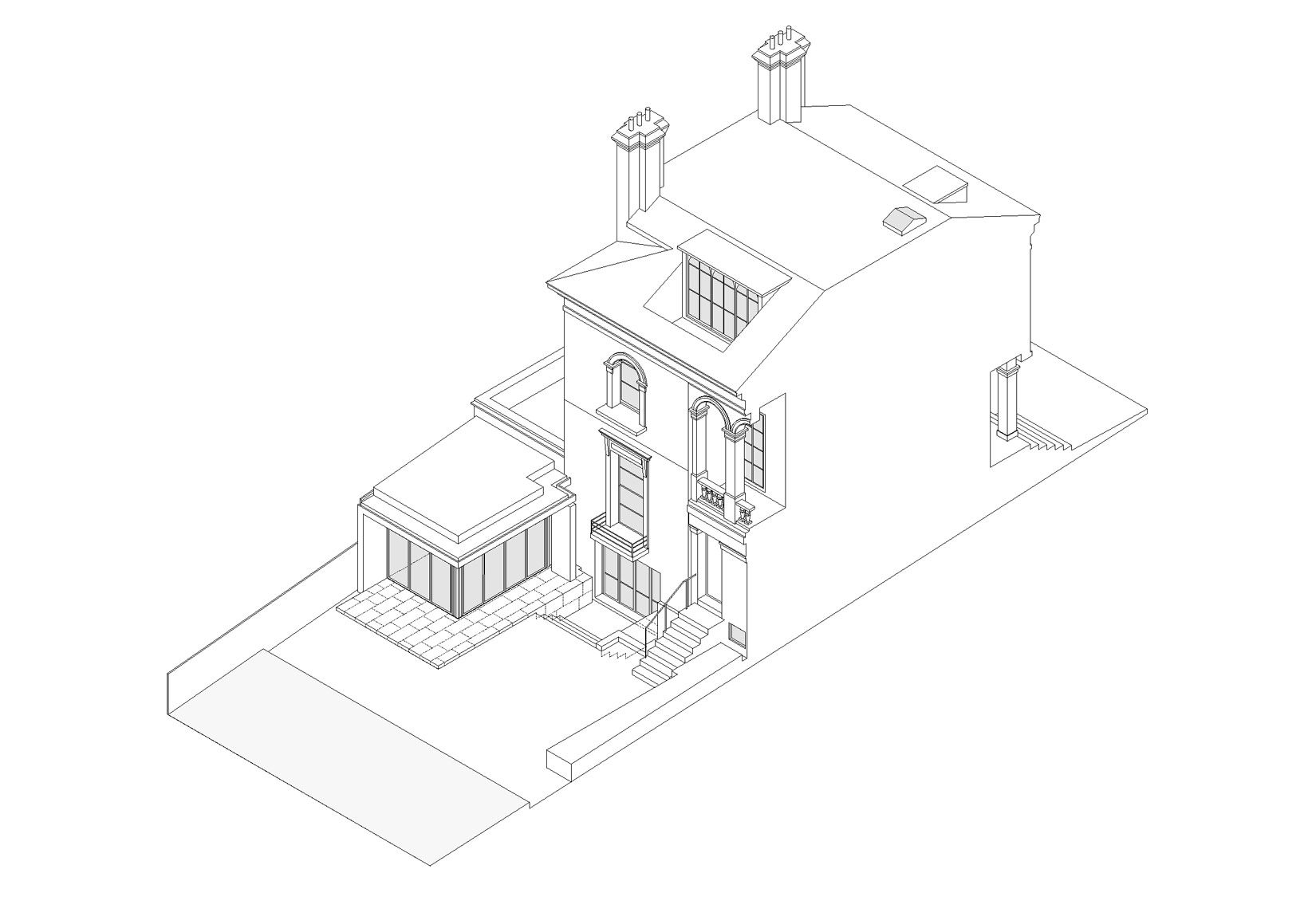

Jonathan Clark has had more than his fair share of experience of navigating between his own ambitions and the reservations of a conservation officer. This is something, he tells us, that you and the architect you’re working with will have to be prepared for when renovating any listed property. To illustrate his point, he then goes on to talk about a project he undertook that involved a lot of back and forth when it came to getting their ideas approved.

“The project involved a front, side and rear extension to a Grade 2 listed villa in North London. The biggest challenge we faced was undoubtedly dealing with the conservation officer. It was a process of negotiation and convincing them that our proposals would materially enhance the building and bring it into the 21st century in a sympathetic way.

Firstly, we met resistance when trying to replace a low-built 1960s garage with a modern alternative. The conservation officer was happy with the proposal to remove the garage but not keen on the concept of its replacement by a modern structure. We argued that the proposed extension would remain entirely subservient to the main house and proposed a lightweight glazed structure to the front and back of the extension. He still wasn’t convinced, so we compromised with a Mannerist elevation – an ornate style that pre-empted baroque in the 16th and 17th centuries – that to the untrained eye could be seen as an original part of the house.”

The conservation officer also refused to allow us to open up the two main rooms at ground floor level, but we were able to track down some very old estate agent sales particulars, which demonstrated that the rooms had been opened up previously.”

Seek the right professionals

“It’s important to have an accredited conservation professional guide you through this process,” Sarah stresses. “These architects have been rigorously assessed so you can rest assured that you’ll be in safe hands.”

You can find architects accredited in conservation on the Architects Accredited in Building Conservation (AABC) register, or you can look for a RIBA Conservation Architect (CA) or Specialist Conservation Architect (SCA) on RIBA’s find a conservation architect service.

“Similarly, other consultants such as structural engineers and mechanical engineers also need to be specialists in historic buildings. It’s also really important to pick specialist builders and craftsmen who have the right skills and experience. Once you have selected a good team, it’s important to trust them and rely on their advice,” Sarah Khan adds.

Working on a listed building can seem like a mammoth task, but ultimately can lead to something truly spectacular.

Sarah has a strong track record of working in conservation as a partner with Roger Mears Architects. She’s a member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), an associate member of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) and a member of the RIBA conservation group. Jonathan heads his own RIBA award-winning architecture firm, Jonathan Clark Architects, and has undertaken some innovative restoration projects in conservation areas in recent years.

Owners of listed properties can find out about Hiscox listed building insurance here on our site.

If your property isn’t subject to the restrictions of listed buildings, then you’ll be able to find the right insurance for your extension through our standard, high quality home insurance.

Very satisfied with the service from Hiscox as always

Very satisfied with the service from Hiscox as always